Inception

- Anthony Faulise

- Mar 7, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Mar 17, 2025

When I was 14, I built an Altair 680b computer from a kit. This was in the earliest days of personal computing. Earlier than that, even. There were instructions. There was a technical manual. There was a CPU manual. But it came with no software, no operating system, no applications. There was not even a hard disk. For the first six months I had the machine, there was no way to save a program; everything was lost the instant I turned the computer off.

Later, I bought a 16K memory card (for $400 IIRC). It came with a text editor, an assembler program, and a debugger program. But, they were on paper tape, and I did not have a paper tape reader. I spent a lot of time looking at the paper tapes I had, longing for a tape reader or an assembler program I could use.

Eventually, I purchased a cassette tape interface, so I could store programs. As it happened, the tape interface came with a 4K Basic interpreter, on cassette tape. So, I finally had a programming language I could use, even if it did take 10 minutes to boot up. For a while, I forgot about an assembler. I wrote programs in Basic.

Years later, I decided to build a Z-80 based S-100 computer. I bought a CPU card, a 64K RAM card, a disk controller and two eight-inch floppy disk drives. But I never got the pieces to work together, and never wrote any code on that machine. By that time I was in college, writing code in C on a VAX-11/750. I was in heaven. I put the Z-80 parts in a box in my parents basement and forgot about them.

Recently, forty years later, I found the box of Z-80 parts in my own attic. I thought about putting them back together. And I realized: I had no operating system, no interpreter or compiler, no software. What would I do with my Z-80?

So, as I began assembling the parts to reconstitute the computer, I decided to write my own Z-80 assembler. From scratch. From first principles. Not copying anyone else’s design or code.

I studied the Z-80 CPU databook. I thought about what I had learned while earning a bachelors and then a master’s degree in computer science. There’s a blog about the assembler. After I finished the assembler, and tested it on a Z-80 emulator (I haven’t finished the Z-80 hardware yet), I happened to re-read a book, “The Soul of a New Machine.”

Soul of a New Machine, by Tracy Kidder, chronicles a small team of engineers at Data General, a mini-computer manufacturer in Massachusetts, working in the late ‘70s to design the next generation 32-bit mini-computer. I’d read the book in college, probably in 1983 or 1984. The first time, it was inspiring, but like a dream. The second time, I wondered “could I have worked on that team, could I have done what they did?”

Only one way to find out...

Here's what I'm hoping to achieve:

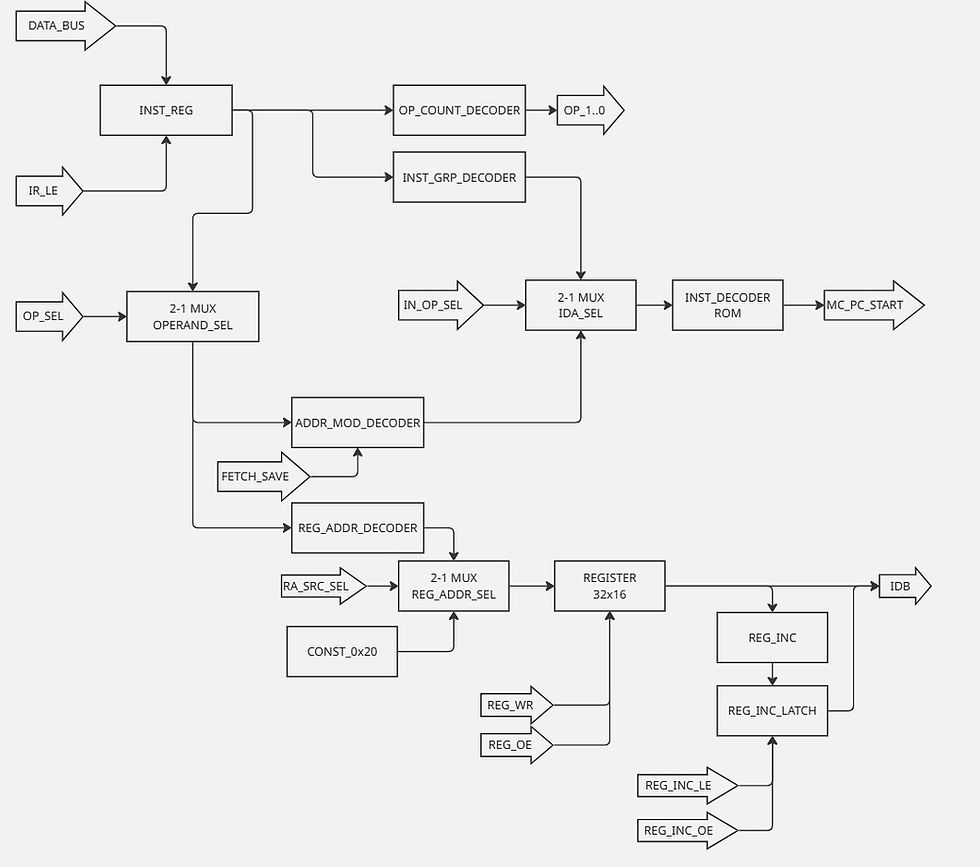

Design and build a micro-coded 16-bit CPU that could easily be extended to 32-bits just by widening the data paths

Include enough support for full-fledged operation of a UNIX-like operating system, meaning

Virtual memory

Supervisor / privileged / user modes

Multi-tasking

Efficient context / process switching

Priority interrupts

DMA

Hard disk

Include a few fun features. At the moment, that means:

Memory cache to keep routine data / instruction fetches off the system bus so the DMA system can do things like file transfer and page swapping efficiently

As much as possible, stick to early-'80s technology like 74LS series TTL

No FPGAs

I do get to use an IDE/ATA disk (ok, it's a cheat)

Comments